L’essere umano ha sempre avuto bisogno di proteggersi la testa dal freddo e dal caldo eccessivi e da eventuali urti. Probabilmente cominciò utilizzando pellicce o grandi foglie e, quindi, imparato a intrecciare ed a tessere fibre animali e vegetali, realizzò i primi cappelli a forma di calotta, caldi per l’inverno, e a larghe tese perché facessero ombra d’estate. Segale e grano, coltivati per ricavarne farine per l’alimentazione, graminacee, erbe palustri e piante a foglia lunga, fornirono la paglia e gli altri materiali per realizzare i cappelli che mantengono immutata da millenni la struttura di base. Nelle stagioni o nei luoghi più caldi i cappelli sono costruiti con fibre naturali, mentre per affrontare le temperature più rigide sono composti di pelliccia. Uno degli esempi più noti è costituito dall’uomo di Similaun, che lega le varie componenti del proprio copricapo con dei lacci fatti passare attraverso dei buchi creati con delle ossa appuntite.

In antico veniva anche usato il feltro. Si dice che le più antiche tracce risalgono addirittura al terzo millennio a.C, epoca in cui il feltro era utilizzato sia dai romani che dai greci, ma i ritrovamenti più antichi sono stati rinvenuti in Siberia. Creato da un intreccio di fibre naturali, si pensa sia stato utilizzato ancor prima della lana. Con il passare del tempo viene adottato da varie popolazioni in base all’area geografica di provenienza e alle loro esigenze: in Russia viene utilizzato per la fabbricazione di stivali, mentre in Mongolia per la costruzione delle tende che fungevano da abitazione. La parola ‘cappello’ inizia a essere utilizzata solo durante il medioevo e deriva dalla parola latina ‘cappa’, indicante un mantello con un cappuccio che veniva utilizzato soprattutto da monache e suore. Ci si inizia ad allontanare dagli scopi primari e spirituali dei copricapi proprio in questo periodo storico. Nel tredicesimo secolo inizia a prendere vita il lavoro del cappellaio e nascono le prime cappellerie. Il commercio della paglia è attestato fin dal 1341 e i produttori di cappelli appartenenti a una categoria professionale sono presenti dal 1574. Negli statuti della Dogana di Firenze del 19 luglio 1577, e pubblicati il 4 marzo 1579, i cappelli di paglia compaiono nell’elenco dei prodotti soggetti a una tassa doganiera.

Fu però ai primi del Settecento che proprio a Signa si cominciò a coltivare il grano non a fini alimentari, ma allo scopo di produrre paglia per fare cappelli. Si trattò di una iniziativa rivoluzionaria, grazie all’intuizione del toscano Domenico Sebastiano Michelacci che consentì al comprensorio fiorentino di diventare il primo produttore di cappelli di paglia di qualità in tutto l’Occidente. Conosciuti universalmente come leghorn perché imbarcati dal porto di Livorno verso i più lontani paesi del mondo, i cappelli fiorentini nelle loro infinite varianti a più giri di finissimo materiale d’intreccio conobbero una fama ineguagliabile imponendosi ovunque quale elemento distintivo nel guardaroba elegante, prima femminile e, quindi, anche maschile. Nacque così il “Cappello di Paglia di Firenze” universalmente riconosciuto come il più venduto nel mondo.

Da sempre Signa, alle porte di Firenze, è sinonimo di lavorazione della paglia e delle tipiche pagliette conosciute in tutto il mondo. Una maestria che da secoli si tramanda di generazione in generazione fino ad oggi.

Signa infatti è tutt’ora la sede delle imprese di cappelli più prestigiose del mondo e la paglia domina ancora. Nella zona infatti, dopo la mietitura, le “rotoballe” di paglia interrompono le distese uniformi dei campi di grano fino a Fiesole, Campi Bisenzio, Sesto Fiorentino, Poggio a Caiano, Brozzi, Quarrata e Prato. Ci ricordano che, una volta estratti i chicchi, anche per gli steli c’è un futuro: non solo nelle stalle ma fino ai guardaroba più sofisticati del mondo.

Nel ‘500 si raggiunse un tale livello di raffinatezza che il Granduca Cosimo I (1519-1574) ne mandò in dono numerosi esemplari a vari sovrani d’Europa, intendendo così omaggiarli del miglior prodotto del Regno. In quel periodo I produttori di cappelli di paglia si riunirono in una categoria professionale e i cappelli di paglia compaiono nell’elenco dei prodotti soggetti a una tassa doganiera.

IL SETTECENTO E “L’INVENZIONE” DELLA PAGLIA TOSCANA

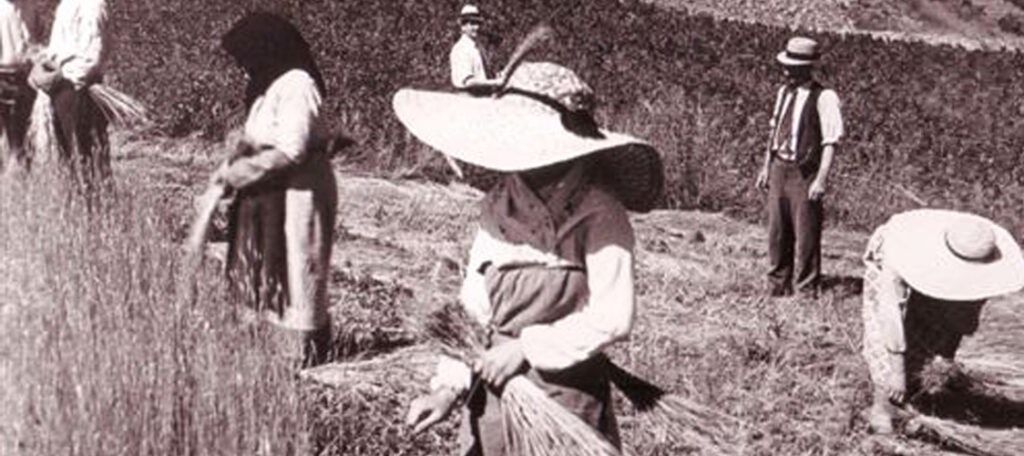

Fino al settecento la paglia destinata ai cappelli era un materiale di scarto proveniente dalla lavorazione del pane. A creare la paglia toscana fu un forlivese (a quell’epoca quindi toscano), Domenico Sebastiano Michelacci che nel 1714, incuriosito dai cappelli intrecciati fatti con steli ricavati dalla battitura del grano dai contadini locali, decise di seminare il frumento al solo scopo di ottenerne paglia per realizzare cappelli e, quindi, ebbe l’intuizione di seminare il grano marzuolo in maniera molto fitta e di raccoglierlo pima che giungesse a maturazione, affinchè la paglia non si indurisse.

Il frumento marzuolo seminato in appositi terreni – detti “alberese” – nel mese di marzo, e maturo a giugno; le piantine per cercare la luce si allungavano tanto da regalare una paglia più lunga e morbida di colore chiaro ed uniforme

Gli steli venivano sbarbati perché la linfa non sgorgasse, ma evaporasse dalle fibre sbiancandole: per questo veniva lasciata per tre giorni e tre notti all’esposizione alternata del sole e della guazza.

Messo a seccare e trebbiato, per subire poi una selezione delle paglie, secondo la grossezza.

Le paglie o magline, vengono quindi sottoposte alla soleggiatura e poi, riunite in mannelli detti manate, passate all’imbianchimento con suffumigazioni di zolfo o bollitura in soluzione di potassa in acqua. Vengono in seguito separate le grosse cannocchie dalle bave più fini, e le prime spaccate in due o più fibre per uguagliarle agli steli più sottili.

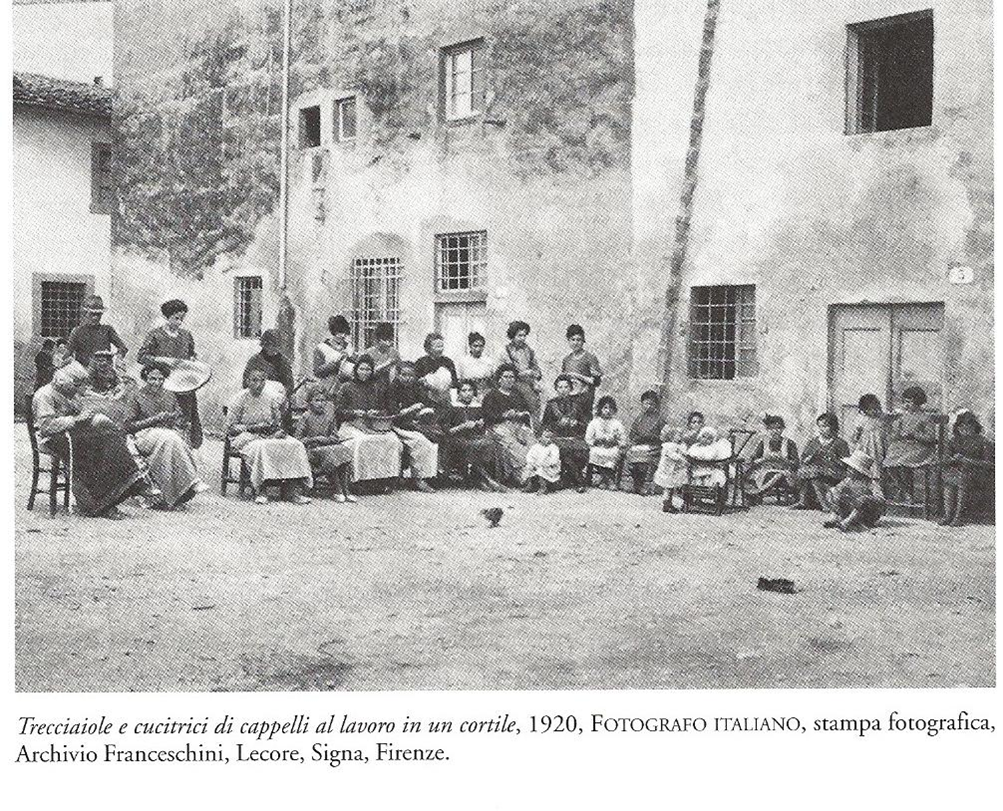

La paglia è così pronta per la lavorazione e viene affidata alle operaie trecciaiole, che devono procedere alla trecciatura.

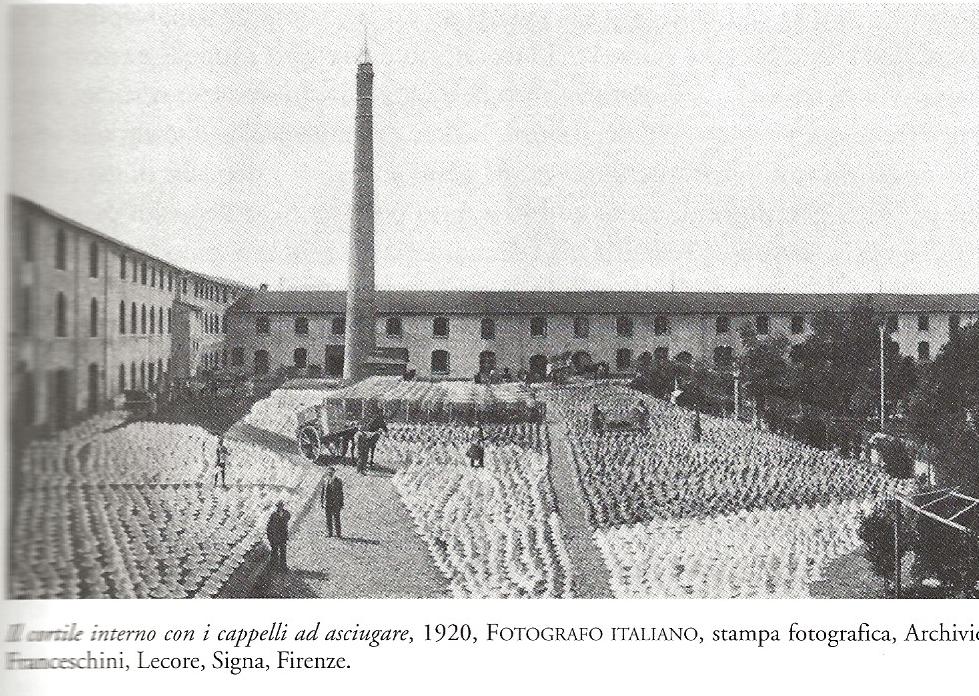

Le trecce, composte da un numero di fili che vanno da 3 a 21 a seconda della grossezza, vengono affidate ad altre operaie che avvolgendole a spira, orlo con orlo sul medesimo piano, partendo dal cocuzzolo per scendere al fianco e all’ala, le cuciono fra di loro, foggiando il cappello nella forma voluta. Le valli dell’Arno, i dintorni di Pistoia e di Firenze, sono celebri in questa lavorazione; e per quanto anche Milano, Venezia e Carpi, in Italia; la Svizzera, la Francia e l’Inghilterra, in Europa; il Giappone e l’America, producano ottimi cappelli di paglia, quello di Firenze ha un incontestato primato che, se gli è in parte conferito dalla irriproducibile varietà della materia prima, in assai maggior misura è frutto dell’abilità delle sue operaie.

Dopo la cucitura, che ora non si fa più a mano come una volta, ma bensì con apposite macchine a punto visibile e a catenella o con le perfettissime e rapide macchine a punto invisibile, il cappello deve essere lisciato, lucidato e apprettato. La lisciatura e la lucidatura sono eseguite o mediante pressione delle varie parti del cappello in un torchio, oppure mediante una stiratura a caldo; l’appretto consiste in un trattamento con soluzione d’acetosella alcalinata e colla di pesce, che dà alle forme, secondo l’uso cui sono destinate, il grado di consistenza voluto.

DOMENICO SEBASTIANO MICHELACCI – Ideatore del “Cappello di Paglia di Firenze” e del made in Italy